What is the legacy of the Bengal School of Art?

The Bengal School of Art, referred to as the Bengal School of Painting, emerged as a significant art movement and style during British India in the early 20th century, specifically from 1900 to the 1930s. It served as a reaction rooted in nationalism and revivalism against the Western art styles that colonial institutions enforced, and it was crucial in shaping modern Indian art. Under British colonial rule, the influence of Western academic realism overshadowed Indian art education, particularly at institutions such as the Government College of Art in Calcutta. Numerous artists from India received training to replicate Western methods such as oil painting, perspective, anatomy, and chiaroscuro. As a result, traditional Indian art forms like miniature painting, folk art, and murals became marginalized.

Birth of Bengal school of Art: a national awakening

Established in Calcutta by Abanindranath Tagore, who is the nephew of Rabindranath Tagore, the Bengal School arose in response to the impact of Western art on India’s artistic heritage. Drawn from Indian customs and pan-Asian artistic influences, especially those from Japan and China, this movement aimed to bring back native styles. The primary figures associated with this school included Abanindranath Tagore, who initiated the movement and gained fame for works like Bharat Mata and The Passing of Shah Jahan. Gaganendranath Tagore introduced elements of Cubism and abstraction into the realm of Indian art.

Nandalal Bose, a student of Abanindranath, gained recognition for his murals and illustrations. He played a key role in the Haripura posters for Mahatma Gandhi at the session of the Indian National Congress, held in 1938 in Gujarat, presided over by Subhas Chandra Bose. Asit Kumar Haldar combined contemporary styles with themes from Indian mythology. Kshitindranath Majumdar, Jamini Roy (in his initial creations), Mukul Dey, Manishi Dey, and Ramkinker Baij, recognized as the trailblazer of ‘’Modern Indian Sculpture’’, were significant figures in this movement. This school drew crucial inspiration from Mughal and Rajput Miniature Paintings, characterized by fine lines, subdued hues, and spiritual motifs, Ajanta murals, which are the historic Buddhist cave artworks in Maharashtra, and Japanese wash methods, brought to India by Japanese artists Okakura Kakuzō and Yokoyama Taikan.

The individuals linked to this Indo-Far Eastern model were Nandalal Bose, Benode Behari Mukherjee, Vinayak Shivaram Masoji, and B. C. Beohar, Rammanohar Sinha, and later their students and several others. Thinkers such as Sister Nivedita and Swami Vivekananda advanced spiritual and nationalist concepts.

Growth of the school: becoming famous

It is noteworthy that the Bengal School gained fame when E. B. Havell served as the head of the Government School of Art in Calcutta from its founding in 1854, when Western art training began. By 1896, he began to advocate for Indian artistic styles and supported Tagore’s methods. In 1897, Abanindranath Tagore began his teaching career at the school, where he started to create a distinctive Indian art style. It eventually acquired a pan-Indian impact via Santiniketan, which was founded by Rabindranath Tagore in 1919 with the establishment of Kala Bhavana, where Nandalal Bose played a crucial role. His notable creation, Siva Drinking the World’s Poison, was an impressive piece. Even though Rabindranath started painting later in his extensive and fruitful life, his concepts had a significant impact on Indian modernism.

Tagore created small, colored drawings using inks in private, drawing on his unconscious mind for inspiration for his primitivism. Rabindranath Tagore’s vision of honoring traditional values, exemplified by themes like rural communities, particularly the Santhal tribes, materialized in the arts-focused institutions of Viswa-Bharati University located in Santiniketan. Rabindranath’s primitivism in public life can be seen as a form of resistance against colonialism, similar to the efforts of Mahatma Gandhi. Focus on mythology, literature, history, and spirituality of India. A style that is soft, poetic, and filled with symbolism, characterized by smooth lines, soothing colors, and watercolor techniques. Dismissal of materialism and realism; emphasis on personal feelings and cultural identity. The Bengal School began to lose prominence in the 1930s due to the emergence of modernist and progressive movements. The series of Krishna Leela was created by different artists who gained recognition for their beautiful and gentle imagery.

Methods and expression: wash, watercolours and tranquility

The Bengal School is known for its use of watercolors, wash painting, natural dyes, and handmade paper, employing methods such as the wash technique. This involves applying layers of thin watercolor to produce gentle, luminous effects. The palette consisted of subdued, natural colors – gentle greens, browns, soft reds, and yellows. No strong differences. The artwork featured fine, smooth lines with little shading. Inspired by Japanese art and miniatures. The subjects included mythology from India, historical events, spiritual beliefs, stories about the homeland, and ethical narratives. The artworks exuded a tranquil and contemplative atmosphere, showcasing idealism, emotion, and spirituality, rather than being completely realistic. The incorporation of Indian aesthetics into contemporary arts by the school acted as a form of artistic expression for the Nationalist movement.

Bengal School – depictions from Indian mythology and history

The Bengal School of Art often showcases Indian mythology and history, especially in artworks that were inspired by the ‘Swadeshi’ movement during the fight for Independence and the creations of Abanindranath Tagore along with his pupils, such as Nandalal Bose and Asit Kumar Haldar. Inspired by Indian folk art, ancient murals, and Mughal miniatures, these artists developed a distinctive style that fused traditional aspects with a contemporary flair.

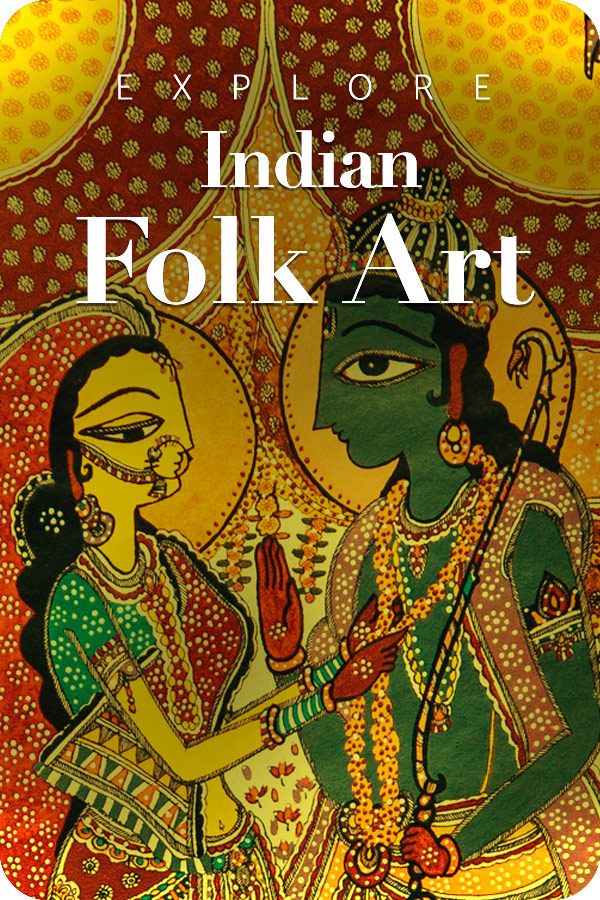

The artists of the Bengal School, such as Nandalal Bose and Asit Kumar Haldar, were significantly inspired by the National movement that sought to enhance Indian art and culture. They dismissed the artistic standards of the West and sought inspiration from native art forms and historical Indian art. They created a unique style that blended aspects of Indian folk art, ancient murals (such as those in the Ajanta and Bagh caves), and Mughal miniatures. The outcome was artworks characterized by gentle, fluid lines, subdued hues, and an emphasis on poetic and romantic subjects, frequently illustrating moments from Indian mythology, such as Radha and Krishna.

The Bengal School frequently depicts Hindu mythology including Radha-Krishna in numerous divine and romantic scenarios, highlighting Radha’s deep devotion to Krishna, their playful exchanges, and the essence of their transcendent love. The Hindu mythological and historical paintings from the Bengal School are viewed as important contributions to Indian art. They showcase a distinctive mix of tradition and contemporary elements, playing a key role in the evolution of modern Indian art. The impact of the Bengal school on the Indian art landscape began to diminish as modernist concepts emerged after independence.

Let us now look at a few paintings from Hindu mythology and Indian history from this iconic Bengal School of Art –

Ashoka’s queen

Abanindranath Tagore (1871-1951) was the pioneer and leading exponent of the Bengal School of Art as already mentioned. He aimed to modernize indigenous Mughal and Rajput traditions in his paintings, countering the Western art influence prevalent in British Raj art schools. His highly influential work became recognized as a national Indian style. This particular print portrays Asoka’s Queen gracefully standing before the railings of the Buddhist monument at Sanchi, built during King Asoka’s reign. This painting captures an important moment in Queen Tissarakshita’s life when she is looking at a wilting Bodhi tree with hanging jewels, thinking that King Ashoka has brought them for other women. She has poisoned the Bodhi plant out of jealousy as it is a favourite of King Ashoka. It is based on an original painting housed in the Royal Collection at Windsor Castle in the United Kingdom.

Paintings by Nandalal Bose

Nandalal Bose (1882-1966) popularly known as the Master Moshai, was a disciple of Abanindranath Tagore. In 1921, Nandalal Bose accepted Rabindranath Tagore’s invitation to become the principal of the art school Kala Bhavan at Visvabharati University in Santiniketan. He also painted a series of posters for the Indian National Congress at Haripura in February 1938 as already mentioned.

Birth of Krishna by Nandalal Bose

In the painting ‘Birth of Krishna’ we see concerned parents, Vasudeva and Devaki as they are trying on a rainy night to relocate their newborn son Krishna to Nanda’s house which is across the Yamuna. The painting captures the seriousness of the situation.

Ascetism of Uma by Nandalal Bose

Parvati embarked on her penance at the sacred site of Gangotri, a place where Lord Shiva himself had meditated. She renounced royal comforts, donned simple attire, and began her austere practices. During summer, she meditated surrounded by fire; in the rainy season, she sat exposed to the elements; and in winter, she immersed herself in icy waters. Initially consuming fruits, she gradually gave up all food, surviving solely on air and water, earning her the name ‘Aparna’. faced scorching heat, biting cold, and torrential rains without flinching, her focus unwavering. Parvati’s penance symbolizes the power of devotion and the belief that unwavering faith can overcome all obstacles. Her story is a testament to the strength of determination and the transformative power of love and devotion.

This painting depicts Uma or Parvati as exposing herself to severe weather conditions. She is facing a biting cold as we see her in the river formed by cold water flowing down the mountains.

Damayanti swayamvara by Nandalal Bose

In the tale of Nala and Damayanti, Damayanti, a princess of Vidarbha, chooses Nala in a swayamvara (a ceremony where a woman chooses her husband). Damayanti had heard about Nala and was captivated by his virtues, even before seeing him. She chose him over the gods, who had disguised themselves as Nala to test her devotion. Nala’s beauty and righteousness impressed Damayanti, leading to their union. The painting here captures the essence of the swayamvara as Damayanti is choosing her husband with a bowed head and a garland, from a group of suitors who all appear to be Nala, however Damayanti chooses Nala, as the disguised Gods reveal themselves on her plea. Nala was known for his beauty, righteousness, and virtue, making him a worthy suitor. His devotion to Damayanti and his willingness to serve the gods further solidified her choice.

Three paintings by Kshitindranath Majumdar

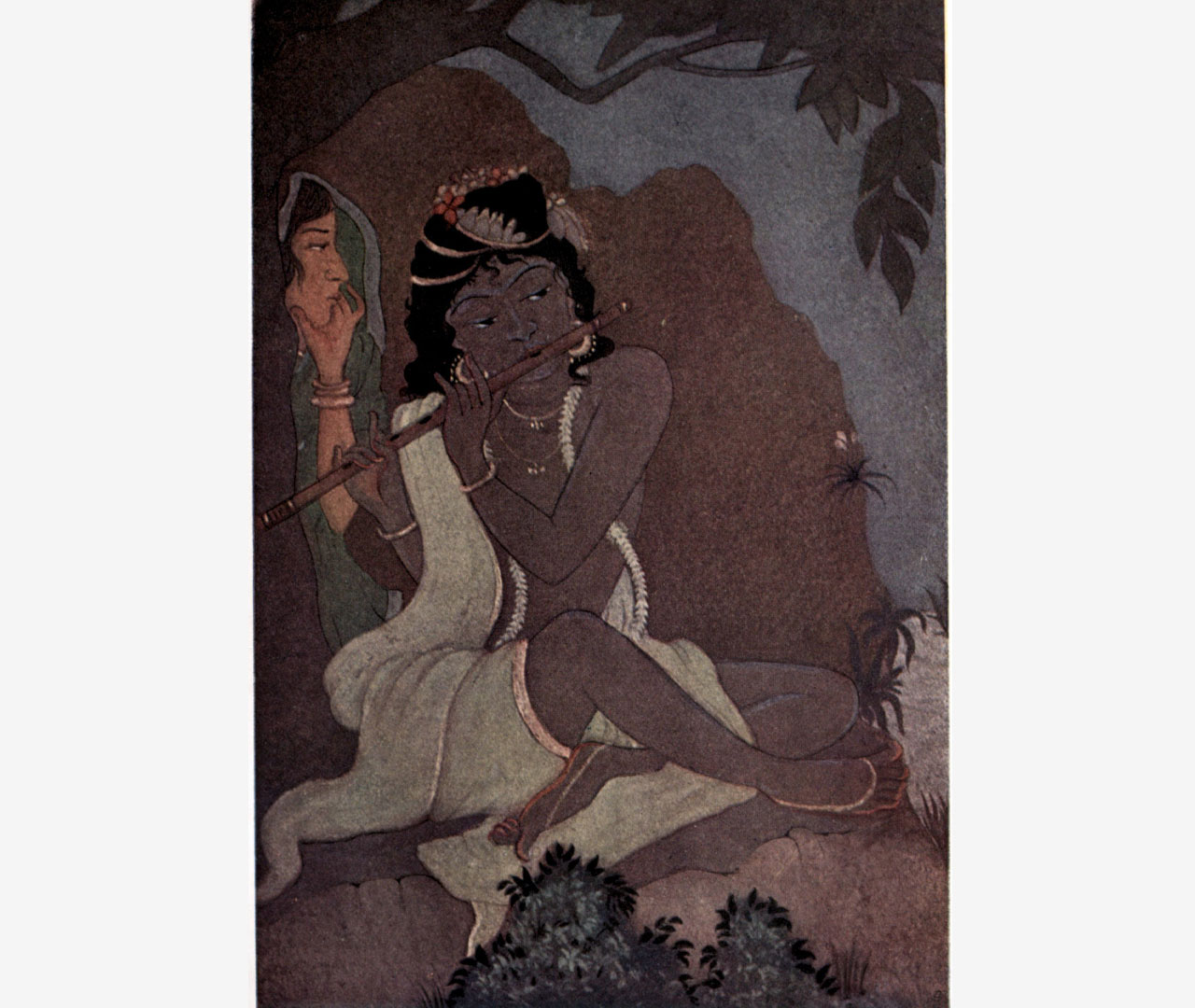

Kshitindranath Majumdar (1891–1975) was a prominent Indian painter and a key figure in the Bengal School of Art, renowned for his devotional and mythological themes. Majumdar was raised in a Vaishnavite household. His early exposure to devotional hymns and local theatre productions, particularly those centered around Krishna Leela, profoundly influenced his artistic sensibilities. Here we see three of his paintings. The first one relates to the divine couple Radha-Krishna – there is a sweetness and romance of this scene, as Radha sits next to Krishna, her gaze filled with love, Krishna plays his flute.

Radha-Krishna by Kshitindranath Majumdar

To gaze on Krishna was my greatest wish,

Yet seeing him was filled with danger.

Gazing has bewitched me, no will remains, I cannot speak or hear.

Like monsoon clouds,

My eyes pour water.

My heart flutters.

O friend, why ever did I see him

And with such joy deliver him my life?……………………………a translation from ‘Vidyapati’s Love songs’ by Deben Bannerjee

Kaliya damana by Kshitindranath Majumdar

The story of Kaliya Daman is a popular episode from the childhood of Lord Krishna, narrated in the Bhagavata Purana. Kaliya was a venomous multi-headed serpent who resided in the Yamuna River near Vrindavan. His presence poisoned the river, causing harm to the environment and the people living nearby. The villagers were terrified, and even Garuda, the eagle and enemy of serpents, could not approach due to a curse. One day, Krishna decided to confront Kaliya. He dived into the river and was ensnared by Kaliya’s coils. Undeterred, Krishna expanded his form and began dancing on Kaliya’s heads, causing the serpent to vomit poison and blood. Kaliya’s wives prayed to Krishna for mercy, and he pardoned Kaliya, instructing him to leave the river and return to his home, Ramanaka Island. Krishna assured Kaliya that Garuda would not harm him, as the imprint of Krishna’s feet on Kaliya’s heads would protect him.

This event symbolizes the triumph of good over evil and the restoration of purity to the Yamuna River. The subduing of Kaliya is reflected in this painting with his wives pleading to Krishna to forgive him. The strength of the snake can be made out by his sheer size, whereas Krishna’s gaze and hold on him shows his might as the halo around his head glows softly depicting his divinity.

The birth of Ganga by by Kshitindranath Majumdar

Ganga is believed to be a divine river, the daughter of Lord Brahma, the creator of the universe. When Lord Vishnu took the Vamana (dwarf) avatar to humble King Bali, he pierced the sky with his toe. From this point, the heavenly waters began to flow. These celestial waters became known as Ganga, residing in Brahmaloka (Brahma’s abode). King Bhagiratha, a descendant of King Sagara, performed intense penance to bring Ganga to earth to purify the ashes of his ancestors who were cursed by Sage Kapila. Pleased by his devotion, Brahma allowed Ganga to descend. Since the force of Ganga’s descent would shatter the earth, Lord Shiva agreed to catch her in his matted hair to break her fall. He released her gently, allowing Ganga to flow as a river on earth. Ganga thus descended to Earth and followed Bhagiratha to the ocean, where she purified the ashes of his ancestors, granting them salvation. Ganga represents purity, salvation, and divine grace, and is revered as both a goddess and a river. Bathing in her waters is believed to cleanse one of sins and aid in attaining moksha (liberation).

The painting here by Kshitindranath Majumdar depicts Lord Shiva catching the forceful Ganga in his locks and then allowing her to flow through his lightly upturned hands. His closed eyes depict his willingness to carry out this deep, sacred and benevolent action for earth.

Paintings by Asit Kumar Halder

Asit Kumar Haldar, who was Rabindranath Tagore’s grand-nephew, started his painting journey early in life after being born in 1890. Later, he received training at the Government School of Art in Calcutta. Between 1909 and 1911, he traveled to Ajanta on an expedition alongside Lady Harringham and collaborated with two other Bengali artists to record the murals found there. Between 1911 and 1915, he served as a teacher at Shantiniketan and held the position of Principal at Kala Bhavan School until 1923, where he supported Tagore in cultural and artistic endeavors.

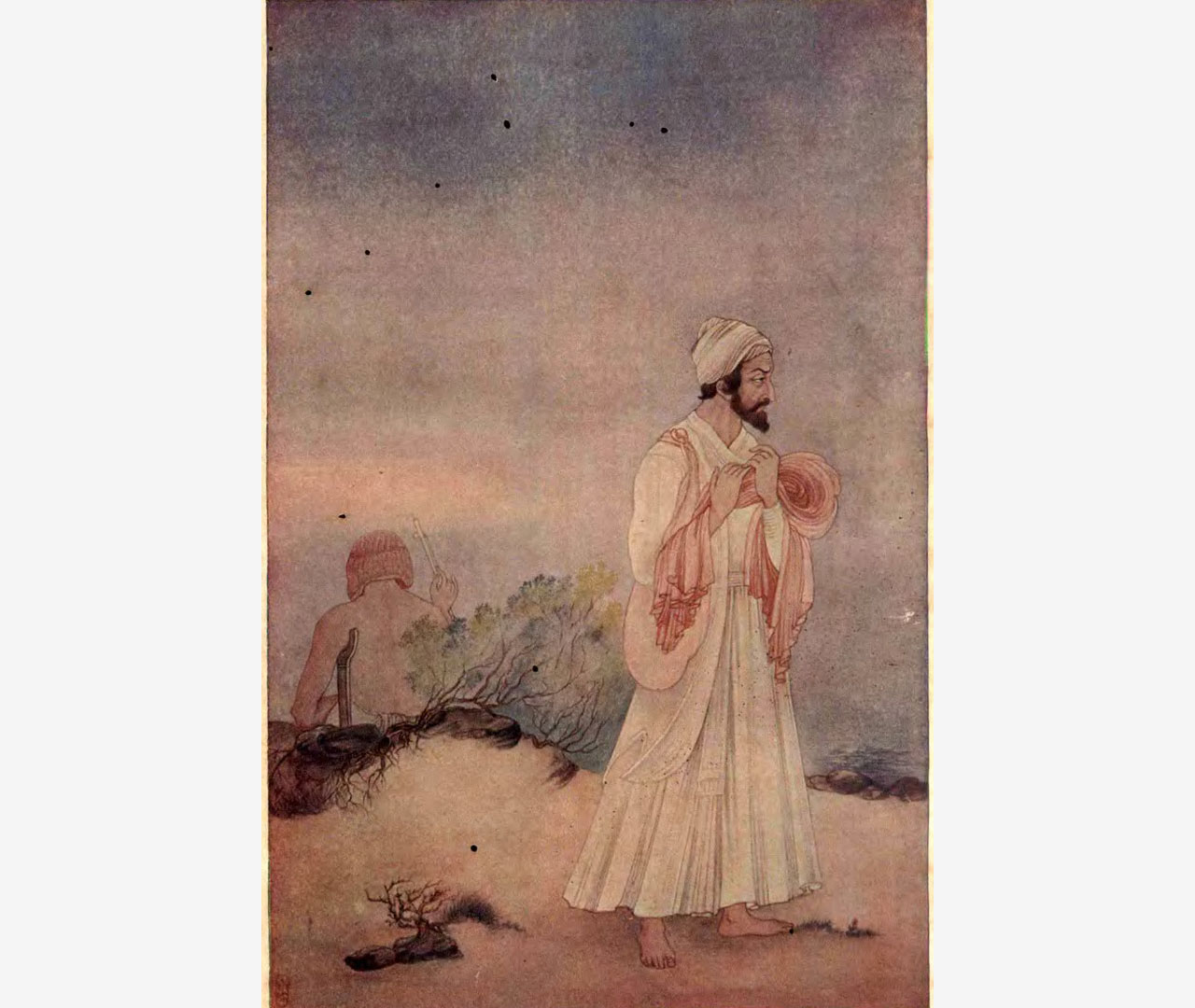

Ramdas and Shivaji by Asit Kumar Halder

In this painting Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, the founder of the Maratha Empire, and Samarth Ramdas Swami, a prominent saint and philosopher, are often associated as a guru-disciple duo. While they did not have a formal mentor-disciple relationship, their lives and philosophies are often intertwined, with some claiming Ramdas Swami played a significant role in Shivaji’s development. Asit Kumar Haldar portrays the Maratha leader Shivaji barefoot in a sombre mood, returning after meeting Ramdas who can be seen seated; which is vividly felt through the rich warmth of the colours. Haldar’s artwork, created in oil, tempera, or watercolors, draws inspiration from the deep stories of Indian mythology and sometimes history as well.

Paintings by Jamini Roy

Jamini Roy, who lived from April 11, 1887, to April 24, 1972, was a painter from India. He is widely recognized as one of the most notable students of Abanindranath Tagore, E. B. Havell. The impact of E.B. Havell and the lectures by Rabindranath Tagore led him to understand that he should seek inspiration from his own cultural heritage instead of Western traditions; thus, he turned to the vibrant folk and tribal art for motivation. The ‘Kalighat Pat’, known for its bold sweeping brush strokes, had a significant impact on him. He shifted from his previous work in impressionist landscapes and portraits, and during the years 1921 to 1924, he initiated his first phase of experimentation using the ‘Santhal’ (a tribe) dance as his foundation.

Rama-Sita and Lakshmana with a golden deer by Jamini Roy

His later paintings are not typical of the Bengal style but a composition in Pat idiom painted in his iconic style is depicted here. Lord Rama, his wife Sita and brother Lakshmana are looking at a golden hued deer which has captured the attention of Sita devi.

Radha-Krishna in Kalighat paintings

Kalighat paintings do not belong to the Bengal school, although they originate from Bengal and is a standalone from influencing artists like Jamini Roy. In the early 19th century, the Kalighat Temple located in the southern area of Kolkata, formerly known as Calcutta, drew many pilgrims and some foreign tourists, in addition to the local residents. The temple grounds offered an ideal chance for artisans and craftsmen to market their products. Included in this group were the patuas, talented artists originating from rural Bengal, particularly from the regions of Midnapore and the 24 Parganas. Traditionally, these artists depicted extensive narrative tales on scrolls made of cloth or hand-crafted paper, with lengths that frequently exceeded 20 meters. This art form was referred to as patachitra, with each part called a pat, which is why the creators were called patuas. Confronted with the need to increase their production speed and inspired by various surrounding art styles, these artists replaced their typical extended narrative approach with individual frames of chouko (square) pat, showcasing one or two figures. Travelers from foreign lands, colonial rulers, and Europeans who visited the city during this era brought back these artworks, described as “perfect” and “portable” for their concise designs, as ‘oriental’ or ‘exotic’ keepsakes. This style features wide, sweeping brush strokes, vibrant colors, and a simplification of shapes.

We can see here a Radha-Krishna done in pat style. Krishna is playing on his flute and Radha stands next to him listening to the music holding the covering of her head.

Radha-Krishna, Kalighat painting, 19th/20th century

Thus, we see that the Bengal school was not only unique during its halcyon days but remains iconic even today with the paintings made during the time, being sold as prints and retrospectives of every major artist being held regularly in India and abroad. They are now preserved in private collections, collections of major Indian and world museums including art galleries.

References –

- https://www.britannica.com/biography/Jamini-Roy (accessed on 4.6.2025)

- https://www.britannica.com/art/Kalighat-painting (accessed on 4.6.2025)

- https://www.visvabharati.ac.in/AsitkumarHaldar.html (accessed on 4.6.2025)

- https://www.visvabharati.ac.in/NandalalBose.html (accessed on 4.6.2025)

- https://www.astaguru.com/artists/kshitindranath-majumdar (accessed on 4.6.2025)

- https://www.britannica.com/biography/Abdur-Rahman-Chughtai (accessed on 4.6.2025)

- https://artoflegendindia.blogspot.com/2010/12/bengal-school-of-arts-heritage-of.html?m=1 (accessed on 4.6.2025)

- https://archive.org/details/LoveSongsOfVidyapatiDebenBannerji/page/n27/mode/1up (accessed on 4.6.2025)

- hinduonline.com (accessed 11.6.2025)

- https://www.lotussculpture.com/blog/hindu-goddess-ganga-birth-descent-earth-shiva/(accessed 11.6.2025)

- https://iskconeducation.org/media_library (accessed 11.6.2025)