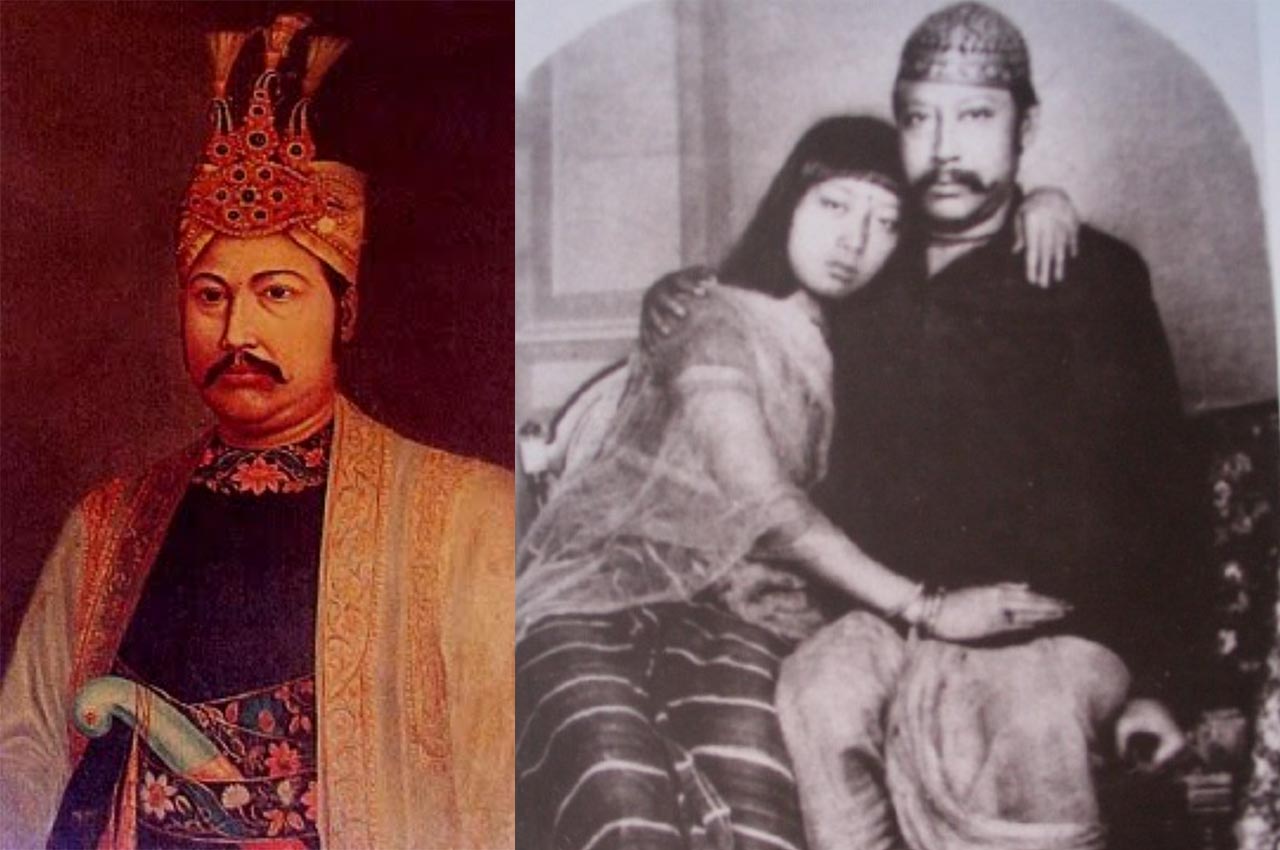

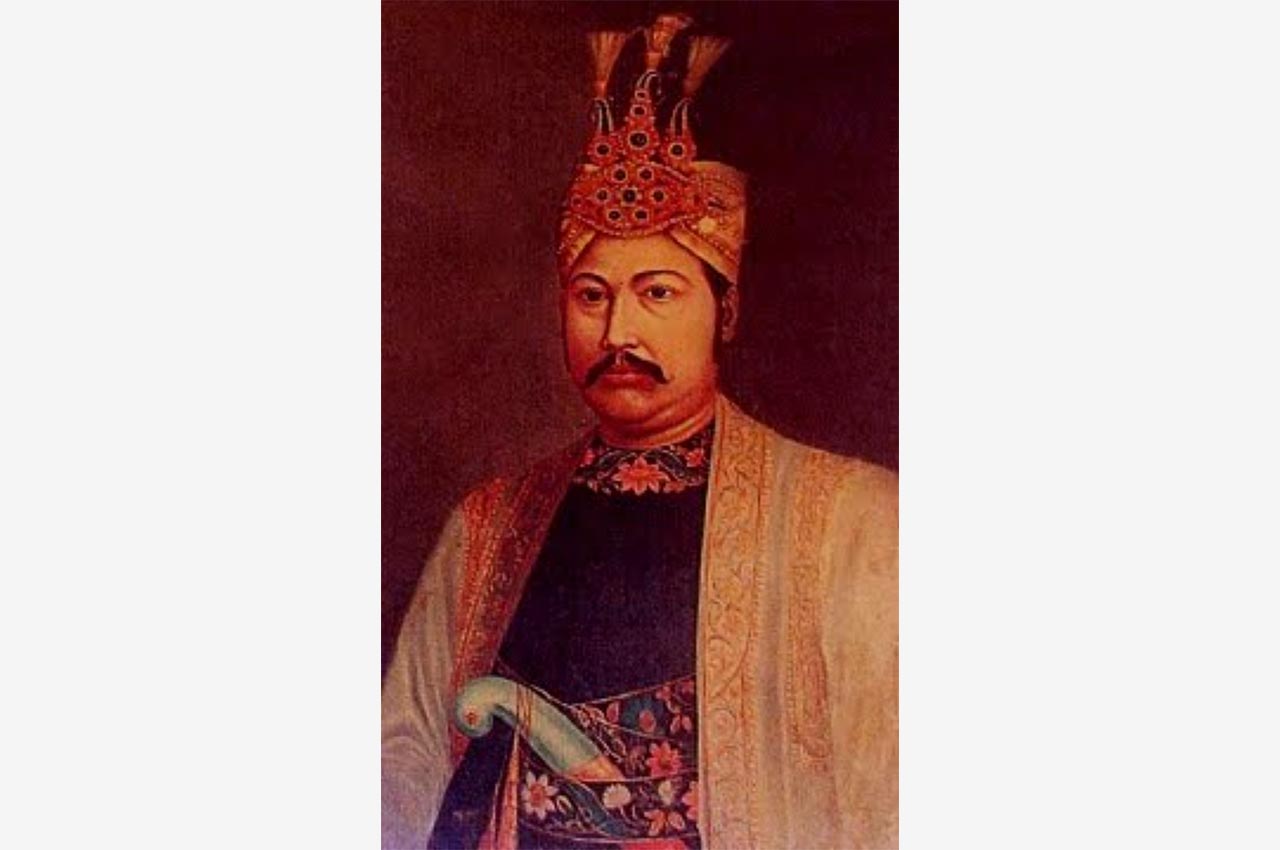

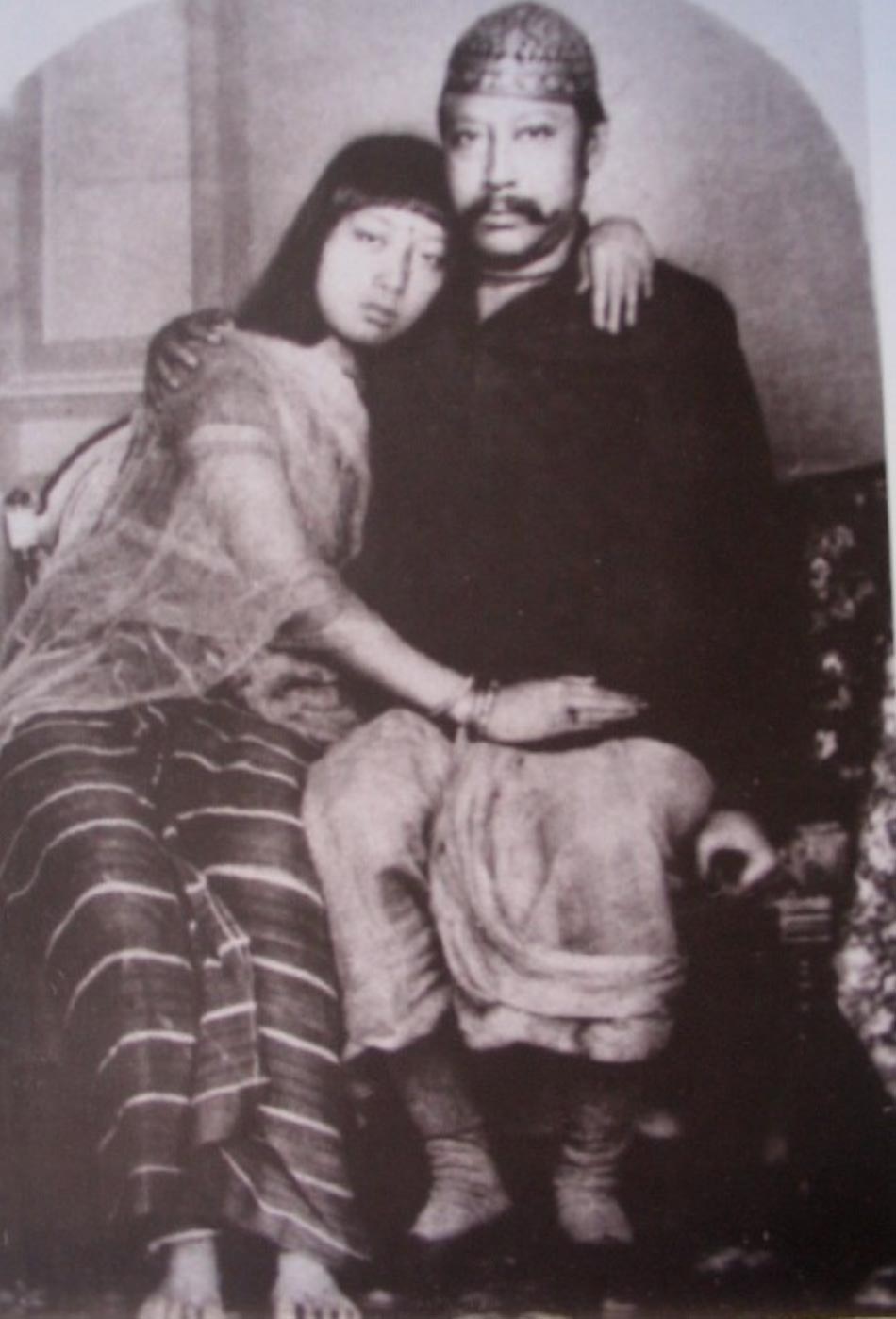

In an age when the world was yet to grasp the essence of photography, one princely figure from a little-known corner of northeastern India redefined time and technology. Maharaja Bir Chandra Manikya of Tripura, also known as the ‘vikramaditya of modern age’, along with his consort, a Manipuri Meitei princess Khuman Chanu Manmohini Devi, not only composed lyrical verses and nurtured music but also captured moments through the lens— leaving behind what many believe to be India’s first “selfie” or “self-shot portrait”. This article traces the multifaceted legacy of this visionary monarch who fused tradition with technology and art with administration to lay the cultural foundations of modern Tripura.

The Beginning of Photography

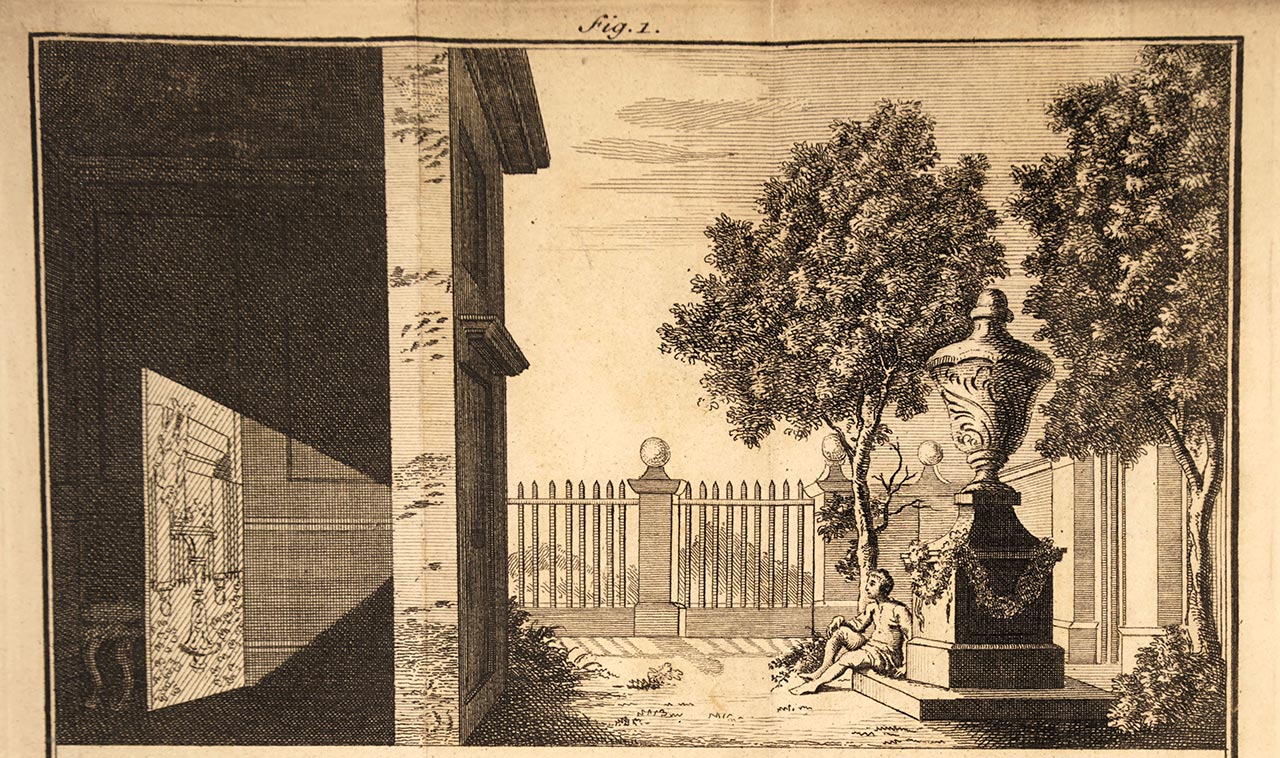

In the 21st century, almost everyone is a photographer with great cameras fixed on our devices. But, long before phones and photo apps, the camera arrived in India as a strange, boxy invention called the ‘camera obscura’, a lens, a mirror, and a sheet of paper, ensnaring light like never before. It was a miracle draped in science. In the early 1800s, two English brothers, Thomas and William Daniell, travelled in India with this mystery box. It was their overseas contemporary, W.H. Fox Talbot, who invented ‘negatives’, allowing innumerable ‘prints’ from a single shot. He called it the ‘calotype’, meaning “the beautiful”. And this invention simply overturned the fate of photography forever.

Arrival of the Camera in India

By the 1830s, cameras were quietly clicking in India. Even Louis Daguerre, the French inventor of the ‘daguerreotype’, left his mark. In Calcutta around 1840, a man named Monsieur Montaino used this technique to capture early glimpses of Indian life. Soon, Photographic Societies sprang up in Bombay, Calcutta, and Madras, backed by the British elite. They published journals, held exhibitions, and turned photography into a ‘fashionable pursuit’. The discourse of photography in India was surely not restricted to a ‘hobby’. In 1839, the British began using photography as a powerful tool. It reflected the subjugated culture of the subjects through the frames of the conqueror. The Indians were photographed by Westerners to strengthen their ideas about the “other”. Alongside, they also captured India’s architecture, mapped its monuments, and catalogued its people. The camera became inseparable in the field of ‘ARCHAEOLOGY’. Men like Alexander Cunningham and Lord Canning saw it as the perfect medium to document India’s ancient past, to preserve what was ‘vanishing’.

The Case of Tripura

In the tranquil corridors of ‘Nuyungma’ or ‘Ujjayanta Palace’, as named by Rabindranath Thakur, during the 1880s, Maharaja Bir Chandra Manikya devised a way to capture an image of himself and his queen, taken using what Bir Chandra’s great-great-great grandson Vivek Dev Burman terms “a long wire shutter control” activated via a pneumatic bulb in the king’s hand as the couple sat facing their camera. This strikingly intimate photograph frames the king affectionately embracing the queen. Such a pose juxtaposes the typical portrayal of a royal pair in a traditional sense. Surprisingly, this experimentation with portraiture resulted in ‘India’s first selfie’, as it did more than freeze a moment in time; it framed a king’s obsession with his craft, innovation, and identity.

A Palace Turned Into a Living Darkroom

He possessed one of the first two cameras that arrived in the Subcontinent (the other was purchased by Raja Deen Dayal, perhaps funded by the Indore state) and was photographing ‘Daguerreotypes’ in the 1860s. He developed all the fresh techniques of photography. The craft of photography in the late 19th century clung to the typical European photographic portraits that were accepted as ‘examples’ and were presented with props, costumes, and painted backgrounds.

Breaking the European Frame

But Maharaja Bir Chandra approached his craft differently. He consciously chose to break the continuum and began experimenting at the Agartala palace. Forthwith, the palace housed a dedicated studio where settings were frequently changed to keep things ‘fresh’. With exposures lasting 10–20 seconds, photography emerged as a collaborative and meticulous process. The photographic materials were sourced from Calcutta, involving a long and tedious journey. The Maharaja soon forged his own “photo darkroom”, mastered the processes of coating and developing, and began importing photographic chemicals and equipment independently.

Building India’s First Royal Camera Club

Maharaja Bir Chandra institutionalized his passion for photography by founding “The Camera Club of the Palace of Agartala” and initiating an annual photography exhibition at the palace. (Memory project) He held the yearly photo exhibition at Agartala to encourage the princes, nobles, and people in the state. His craft became so renowned that the American photographic journal, namely “Practical photographer”, published the illustrated biography of Maharaja in one of its publications. In a holistic sense, it was during his reign that the true beginning of Tripura’s modern age occurred.

When the Queen Became a Photographer

In the May 1890 edition of the Photographic Society of India’s journal, a letter penned by Radharaman Ghosh, secretary to the Maharaja of Tripura, titled “The Camera Club of the Palace of Agartala,” offered insights into a royal photographic endeavour. Though signed by Ghosh, the content was likely dictated by Maharaja Bir Chandra Manikya himself and accompanied a set of photographs submitted to the journal. Interestingly, some of the images were credited to the Maharaja, others were said to have been taken by his consort, Maharani Manmohini. This resurfaced in Siddhartha Ghosh’s landmark 1988 book, Chobi Tola: Bangalir Photography Chorcha. Ghosh highlights that Maharani Manmohini not only took photographs but also printed most of them, while the Maharaja handled much of the developing. Each image, he notes, bore a distinct identifier marking its creator. Therefore, Maharaja’s passion for photography transcended the boundaries of his personal pursuit, as his third wife, Monmohini Debi, became an amateur photographer under his guidance. Manmohini seems to be the first Indian woman credited with taking photographs, but it is her bhadramahila contemporary Sarojini Ghosh who is recognised as the first Indian woman professional photographer.

The Sons Who Carried the Lens Forward

Some of his platinum palladium prints were part of a 2019 exhibition titled The Tripura Project curated at the Mangalbag Gallery, Ahmedabad, by Tilla, a design studio founded by Aratrik Dev Varman, one of the king’s descendants, including another “selfie” with his first wife, Bhanumati Devi. Bir Chandra’s sons were also avid photographers, carrying their father’s legacy forward. Samarendra (Bara Thakur) was a prolific photographer who regularly submitted his photographs to competitions in England. His work and writings on photography are well documented. One of his most renowned photographs—a portrait of a tribal girl—is preserved at the British Library. Samarendra even experimented with techniques to preserve negatives under the challenging hot and humid conditions of India. His father famously remarked, “Samarendra’s paintings and photographs were near flawless.” Another son, Maharaja Radha Kishore Manikya, was likewise a passionate photographer and succeeded to the throne in 1897. Unfortunately, no negatives of their photographic works have been discovered to date.

| Important Aspect | Mentionworthy Details |

|---|---|

| Royal family’s engagement | Bir Chandra’s sons were avid and skilled photographers |

| Samarendra (Bara Thakur) | Prolific photographer; submitted work to competitions in England. Experimented with techniques to preserve negatives in hot/humid conditions. His renowned portrait of a tribal girl is at the British Library. |

| Maharaja Radha Kishore Manikya | Passionate photographer; succeeded to the throne in 1897 |

| Father’s Remark | Bir Chandra considered Samarendra’s paintings and photographs near flawless |

| Loss of Archival Material | No negatives of their photographic works have been discovered to date |

Key Highlights

- Bir Chandra Manikya’s sons carried forward his pioneering interest in photography.

- Samarendra (Bara Thakur) gained recognition internationally for his photographic submissions to England.

- His iconic portrait of a tribal girl is preserved in the British Library.

- He explored techniques to protect photographic negatives in harsh tropical conditions.

- Maharaja Radha Kishore Manikya was also deeply passionate about photography, alongside his royal duties.

- Despite their contributions, none of their original photographic negatives have survived.

Takeaway

The photographic pursuits of Tripura’s royal heirs reflect a remarkable blend of artistic curiosity and technological experimentation. These were rare qualities in princely households of the time. Their engagement with the medium was not only leisurely; it was innovative and internationally relevant. The loss of their negatives is an unfortunate gap in India’s visual heritage, for their works could have offered invaluable insights into the socio-cultural landscape of Northeast India during the late 19th century. Their legacy, however, stands as a testament to a dynasty far ahead of its time.