Decentering Art History through Material Knowledge

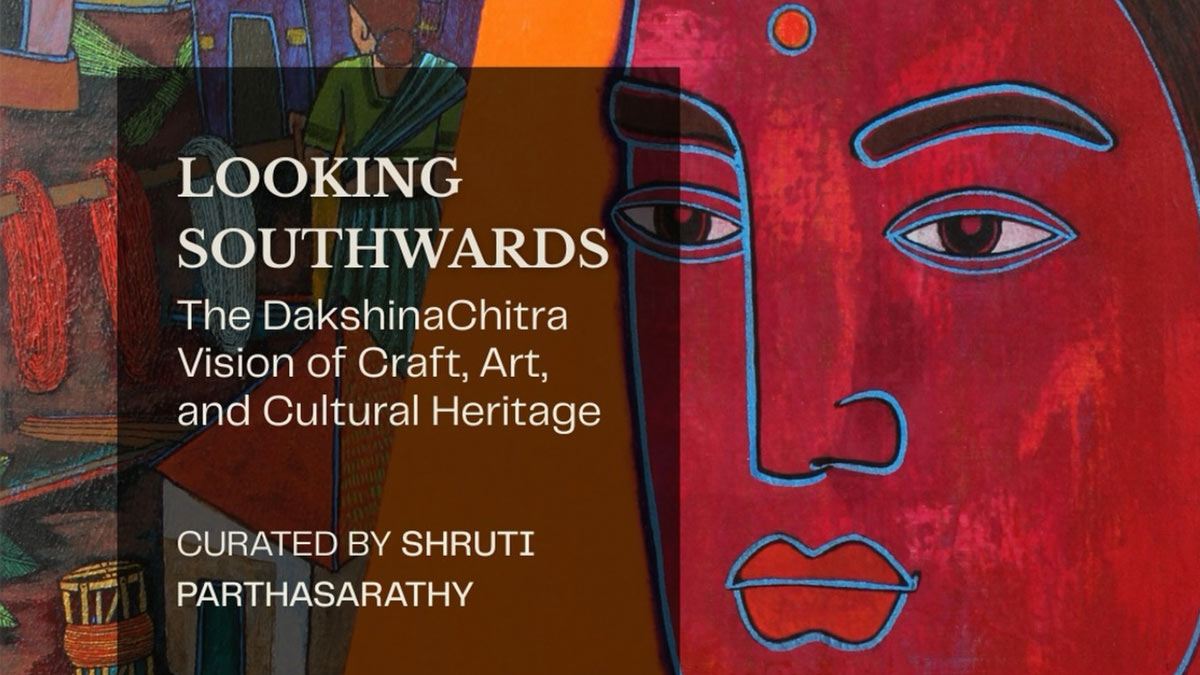

For the better part of a generation, the nucleus of the mainstream chronicon of Indian art history was restricted to the Indo-Gangetic plains (North India). It primarily highlighted the patronage of the art by the imperial courts and was dominated by what can be identified as “northern aesthetics.” To display the other side of the coin, DakshinaChitra is poised to instate an exhibition titled, “Looking Southwards: The DakshinaChitra Vision of Craft, Art, and Cultural Heritage.” Curated by Shruti Parthasarathy, this showcase of exhibits contests the status quo and inherently looks Southwards. “Looking Southwards” in the context of Indian art and heritage does not refer to a geographical reconfiguration; it is noetic and epistemic in nature.

This exposition aims to situate the southern Indian aesthetics in a self-contained and critical juncture of global attention. It also looks forward to subverting the narrative of positioning the South as the peripheral cultural zone and setting foot to unveil its true cultural zeal. The exhibition will be on view at the Varija Art Gallery, DakshinaChitra, Muttukadu (ECR), running from January 9 to February 15 and March 9 to March 30. Drawing from DakshinaChitra’s extensive collections, the exhibition presents objects not as inert artefacts but as carriers of histories, labour economies, and intergenerational memory systems.

Understanding the Southward Gaze

A huge chunk of Indian history views the South through a very “selective” lens of temple architecture, classical dance forms, and devotional iconography of certain distinct phases. This tendency creates a huge lapse of everyday material practices, vernacular aesthetics, and craft lineages that are subsequently marginalized and gradually lost within the folds of the past. Therefore, looking southwards means acknowledging the unique sociopolitical and ecological factors that shaped Southern Indian craftsmanship.

Actually, looking southwards poses contrarian views by accentuating craft as a form of knowledge, rather than a commodity. It invests in a huge corpus of craftsmanship ranging from the intricate bronze casting of the Chola period to the vibrant weaving traditions of the Coromandel Coast, and more. In this context, the “south” appears as a depot of techniques that have survived through community-held knowledge rather than just state-sponsored patronage. It subtly breaks the binary of the “traditional vs. modern” and looks beyond it by introducing the “southern” element.

Craft as Knowledge, Not Ornament

The exhibition at DaskshinaChitra rejects the pure commodification and decorative categorisation of craft. Instead, they situate it within a bigger umbrella of museology, anthropology, and heritage politics. The displayed exhibits are contextualized and validated through their associations with social lives. This aspect makes them a vital node of the ritual, domestic, and market economies. This reflects the contemporary scholastic traditions regarding material culture. This recognizes craft as a repository of technical intelligence and socio-cultural negotiation.

The curatorial narrative directly opposes the narrative of one-region-dominated craft narratives and questions regional representation. Unlike other narrative buildings, this exhibition breaks through the homogenization of “South Indian Culture.” It shifts the foci to multiple cultural segments and offers a pluralistic understanding of the South as a mosaic of languages, castes, occupations, and rituals. In this way, they probe into how museums and heritage institutions construct narratives, what they choose to display, what remains invisible, and how authority is exercised through curation.

Glimpses of The Exhibition

| Exhibition | Details |

|---|---|

| Title | Looking Southwards: The DakshinaChitra Vision of Craft, Art, and Cultural Heritage |

| Curator | Shruti Parthasarathy (@lafzbeylafz) |

| Venue | Varija Art Gallery, DakshinaChitra, Muttukadu, ECR, Chennai |

| Primary Phases | January 9 – February 15 & March 9 – March 30 |

| Opening Ceremony | January 9, 2026, at 4:00 PM |

| Focus Area | Material knowledge, regional representation, and heritage-making |

| Core Theme | The South as a site of material knowledge and cultural production |

| Approach | Interrogates representation, heritage-making, and curatorial authority |

The DakshinaChitra Intervention

View this post on Instagram

DakshinaChitra has successfully earned an image of a “living” cultural centre. It is not a museum of static objects, but an evolving institution with a forward-looking vision. By orchestrating this exhibition, they have enhanced the bargaining power of the South in not being a static relic of the past but a dynamic agent of contemporary culture. The exhibition functions not merely as a showcase of collections but as a discursive platform that questions the politics of heritage-making itself. It echoes current academic conversations around decolonising museums and rethinking regional knowledge systems that challenge Eurocentric hierarchies in art history.

Key Highlights

- Positions South India as a critical intellectual and material landscape rather than a cultural “periphery.”

- Draws extensively from DakshinaChitra’s collections, foregrounding living craft traditions.

- Challenges decorative interpretations of craft by framing it as embodied knowledge.

- Engages with contemporary debates on decolonising museums and heritage narratives.

- Encourages reflection on curatorial power, representation, and institutional storytelling.

- Bridges traditional craft and contemporary artistic practices.

- The showcase features objects that bridge the gap between daily utility and high art.

- The exhibition explores the chemistry of dyes, the physics of loom-work, and the spiritual geometry behind southern architecture.

- It questions who gets to decide what is “heritage.”

- By placing craft on the same pedestal as “fine art,” Parthasarathy challenges the colonial hierarchies of aesthetic value.

- Beyond the objects, the exhibition utilizes narratives to connect the viewer with the anonymous artisans whose hands shaped the southern identity.

Takeaway

By positioning the South as a “critical site,” the exhibition forces the viewer to confront their own biases regarding what constitutes “sophisticated” art. It challenges visitors to rethink how they understand “tradition,” not as a static inheritance but as a dynamic, contested, and deeply political terrain of knowledge. It is a bold statement that the heart of Indian cultural production has always had a strong, southern pulse. This exhibition does not merely display culture; it reframes it, compelling viewers to confront the epistemological hierarchies that continue to shape how Indian art and heritage are studied, curated, and valued.