Colonial Imagery and the Construction of Indian Identities

The term “Typecast” is brought into play in the modern context, while relegating or compartmentalizing a certain group of people into specific chambers of presumed frames. However, these attestations are often punctuated by errs and prejudices. To mitigate these with a historically corrected vision, DAG is about to craft an exhibition titled “Typecasting: Photographing the Peoples of India, 1855-1920,” at Bikaner House, New Delhi, from January 30 to February 14, 2026.

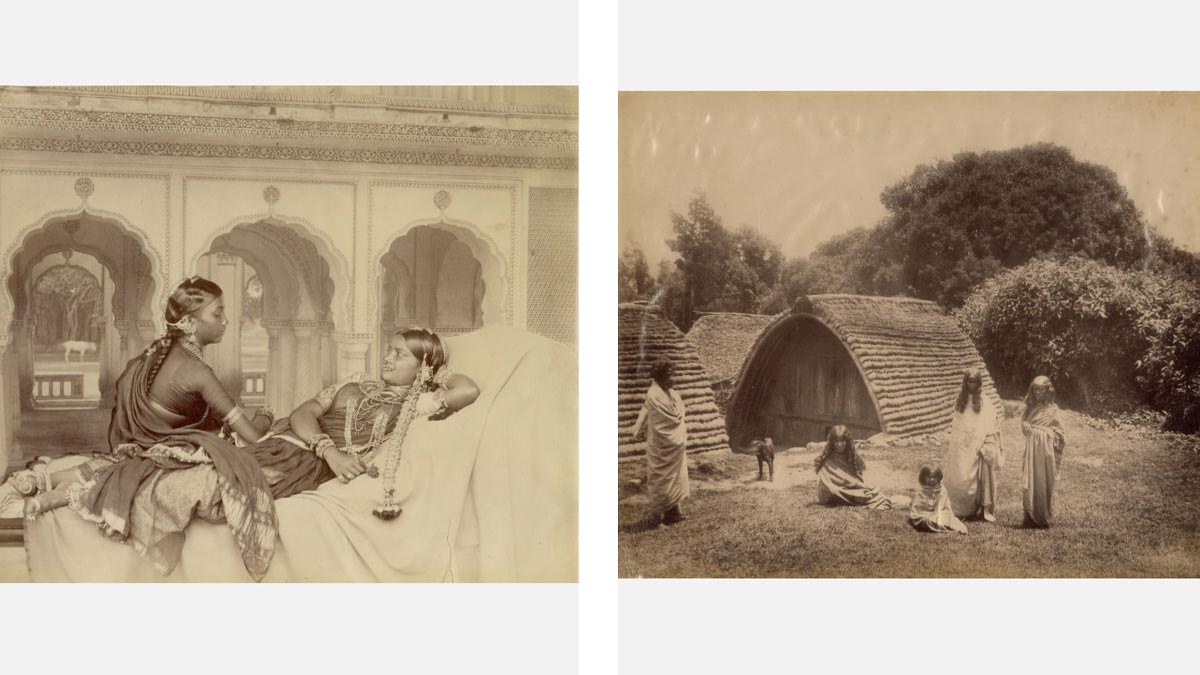

The intellectual space in which the exhibition swoops is how the British lenses clicked and visualized the socio-culturally diverse communities of India. The exhibition will exhibit one of India’s largest collections of early ethnographic photographs, which were used as a tool to categorize people under distinctive labels. It interprets the colonial gaze of the 19th-20th centuries and de-classifies the British psyche of classifying Indians based on a visual tradition.

The corpus of images also displays the paradigm-shifting “The People of India” (published between 1868 and 1875). It was an eight-volume photographic series compiled under the direction of John Forbes Watson and John William Kaye. These images were clicked by leading photographers like James Waterhouse, William Willoughby Hooper, Francis Frith, Skeen & Co., and Nichols and Sons. The stated agenda of these white men was to create a visual catalogue of the heterogeneous tribes, castes, and communities. What they executed and compiled put people into rigid categorical receptacles for “scientific” observation. However, the true intention was to understand the actual diversity and divergent factors of the population to control them through manipulative measures.

The typecasting of the Indian people was carried through the appellations of caste, occupation, and perceived character traits, putting millions of folks into socio-political minaudières that moulded their model of governance and administration for generations to come. The corpus of these snapshots reveals a lot about the political ambitions of the colonizers and expatiate their way of utilizing aesthetics to exert political control.

A Quick Glimpse Into The Exhibition

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Venue and Dates | Bikaner House, New Delhi; January 30 – February 14, 2026 |

| Central Archive | The People of India photographic series (1868–1875) |

| Curatorial Focus | Colonial ethnography and visual categorisation of Indian communities |

| Range of Media | Albumen prints, silver gelatin prints, cartes de visite, photo albums |

| Historical Span | Images from 1855 to 1920, tracing early photographic evolution in India |

| Critical Inquiry | Challenges the presumed objectivity of colonial photographic documentation |

| Colonial Ethnography | Photography used by British officers such as J. Forbes Watson and John William Kaye to document tribes and castes for administrative “intelligence” |

| The “Scientific” Gaze | Subjects were often posed and stripped of individuality to represent generic human “types” under the guise of scientific truth |

| Programming Parallel | Colonial typecasting simplified complex identities, similar to how data typecasting forces variables into fixed formats |

| Impact on Modernity | These classifications contributed to rigid caste and communal identities that continue to influence Indian sociology and politics |

Key Highlights

- The exhibition is one of the largest showcases of early colonial ethnographic photography ever mounted in India.

- The exhibition features works from 1855 to 1920, a period where photography transitioned from a rare novelty to a powerful tool for the British Raj to “know” its subjects.

- Works include a wide array of photographic formats, from albumen and silver-gelatin prints to postcards and cabinet cards, that chart technological and aesthetic developments over decades.

- Central to the display are the folios from The People of India, which attempted to present a comprehensive visual index of India’s “types.”

- Research shows that subjects were frequently photographed against neutral backgrounds, removing their personal context and turning them into “specimens” rather than individuals.

- Photographs in the exhibition encompass communities ranging from the Lepcha and Bhutia tribes of the Northeast to the Afridis of Sind and the Todas of the Nilgiris, as well as urban social groups including Parsee and Gujarati communities.

- The curatorial narrative emphasises that photography was neither purely scientific nor objective but played an active role in shaping colonial power relations and social hierarchies.

- Visitors are encouraged to consider how visual categorisation informed British administrative practices and influenced contemporary understandings of Indian identities.

- Similar ethnographic projects were carried out by colonial powers in Africa and the Americas, showing that “typecasting” was a global phenomenon used to justify imperial rule.

The Legacy of the Colonial Image

This phenomenon of typecasting is not restricted to the display of vintage pictorials; it is an interrogation of the “Anthropometric” method, meaning to scientifically study the measurements and proportions of the human body. These initiatives were also related to the notions of “scientific racism” of the 19th century. Methods like these were employed to transform a diverse population into legible, manageable data.

For instance, the colonial anthropometrician, Sir Herbert Hope Risley, stated that India was not a single nation but a collection of fragmented “racial” groups. By proving India was “irretrievably fragmented,” the British could argue that their rule was indispensable to prevent anarchy. Risley subscribed to the fact that “caste is race,” and he deployed the attained measurements to “prove” that the caste system was a rigid, biologically-driven hierarchy rather than a social one.

The Brits used measurements like the nasal index (nose width vs. height) to determine Indians’ proximity to the European standards. These photographs were the visual evidence used to support the “Martial Races” theory. This theory was propounded by the colonizers in the post-1857 period. It was a pseudo-scientific theory devised by the British to reorganize the colonial military and stabilize the foundation of crown rule. It was an essential tool to maintain the “divide and rule.” The Brits labelled some communities that remained loyal as “naturally warlike.” The groups that rebelled got labeled as “unfit for battle.” This was a manipulative tactic to ensure that the colonial army comprised groups trusted by the colonizers. It marked a selective exclusion of educated, politically active Indians from military service to prevent future uprisings.

Today, when people look at these images in the post-colonial era, an intrinsic juxtaposition resurfaces. A grappling situation is confronted by the spectator, where they observe the intent of the whites clashing with the dignity of the subjects who were photographed. Even within the rigid “types” of a Brahmin priest, a Rajput warrior, or a Banasree laborer, the eyes of the subjects often betray a resistance to the box they were being placed in.

Further Scrutiny

In the showcasing of these images, they will be accompanied by descriptive letterpress that confirms the racial and cultural assumptions. This enables the viewers to analytically understand the colonial vision in depth. DAG does not aim to neutralize or dilute the formation of these images and thus took a very judicious step in keeping it categorical, just as how Watson, Kaye, and their collaborators shaped stereotypes. It stands out because DAG has effectively paired the photographs with thoughtful explanations that bring in different perspectives and help people see through it.

The range of materials exhibited incorporates studio portraits, albums, and postcards. They also reveal the circulation of these images. Some postcards, meant for Indian buyers, celebrated the country’s heritage, while others, sent to Europe, encouraged exotic or hierarchical interpretations of Indian communities.

Also, other photographers featured in the exhibition, such as Samuel Bourne and Lala Deen Dayal, operated within the ambit of the colonial sphere of perceptions. Samuel Bourne’s aesthetics, for instance, bridged the thirst of both the East and the West. Bourne was acknowledged for the clarity anf composition of his images and they shaped to a great extent of how the foreign audiences actually imagined India. His photographs rarely touched the niche of the trivial everyday life of India, and focused on the grand historical monuments, dramatic landscape, etc.

On the other hand, Lala Deen Dayal was one of India’s earliest and most accomplished indigenous photographers. He worked as the court photographer for the Nizam and also documented the vividness of India’s civic life by covering public events, architecture, and aristocratic elements as well. He stood at the other end of the plane, as an Indian responding to the colonial photographers.

Takeaway

DAG’s upcoming exhibition is going to emerge as a mnemonic that the way people label others is rarely about the person being labeled and always about the person doing the labeling. It opens a liberal space inviting critical introspection into the existance of visual culture in India.

The exhibition diorients the myths infused by the colonizers upon Indians by welcoming a more composed debate around the colonial photography with a contemporary lens. Whether it is a colonial administrator in 1860 or an algorithm in 2025, the act of “typecasting” strips away the zeal that make us human.

Their wish to create a “manageable” India, actually created a fragmented one. The core essence of revisiting these pictures is to refresh the stereotypes and prejudices that still exists in the larger mental sphere of Indians. Identities are extremely fluid and multifaceted; they change with social, economic, cultural, and political influxes.

By understanding how we were once “typecast” by an external power, we gain the clarity to reject the modern stereotypes. The exhibition not only enriches art historical discourse but also contributes meaningfully to broader conversations about post-colonial identity and archival justice. History, in this case, is not just a record of the past, but a mirror reflecting our own lingering biases.As Robertson Davies said, “The eye sees only what the mind is prepared to comprehend.” DAG truly steps into the psyche of the colonial times and re-shaping the modern Indian conscience, letting people become more and more inclusive.