The story of global trade is often narrated through economic policies, ledgers, and cargo manifests, but ironically, in the colonial phase in India, it was more rooted in small articles, paper labels, etc. The exhibition “Ticket Tika Chaap: The Art of the Trademark in the Indo-British Textile Trade,” at the Museum of Art & Photography (MAP), Bengaluru, dives deep into such forgotten artifacts as glossy, postcard-sized paper labels, known as tikats, tikas, or chaaps, that were affixed to lengths of British and Indian mill-made cloth sold across the Indian subcontinent from the late 19th to the mid-20th century. These small labels bore the footprint of the economic empire of the colonialists and also became a means to reflect on the nature of political ideologies that existed at that time. Scheduled to run till February 15, 2026, this exhibition is curated by Nathaniel Gaskell and Shrey Maurya.

The Birth of Branding on the Subcontinent

In the late 19th century, the British products of the textile mills in Manchester flooded the vast Indian market with millions of yards of machine-spun cotton. While this reflected the affluence of British goods in India, it also posed a commercial issue of how a merchant could distinguish their mass-produced bale of cloth from that of a competitor. The Indian market was indeed a booming sphere. Still, the majority of people purchasing the British goods were illiterate, and thus a presentation of visually relatable hallmark was the need of the hour. The solution that they came up with was creating a textile ticket.

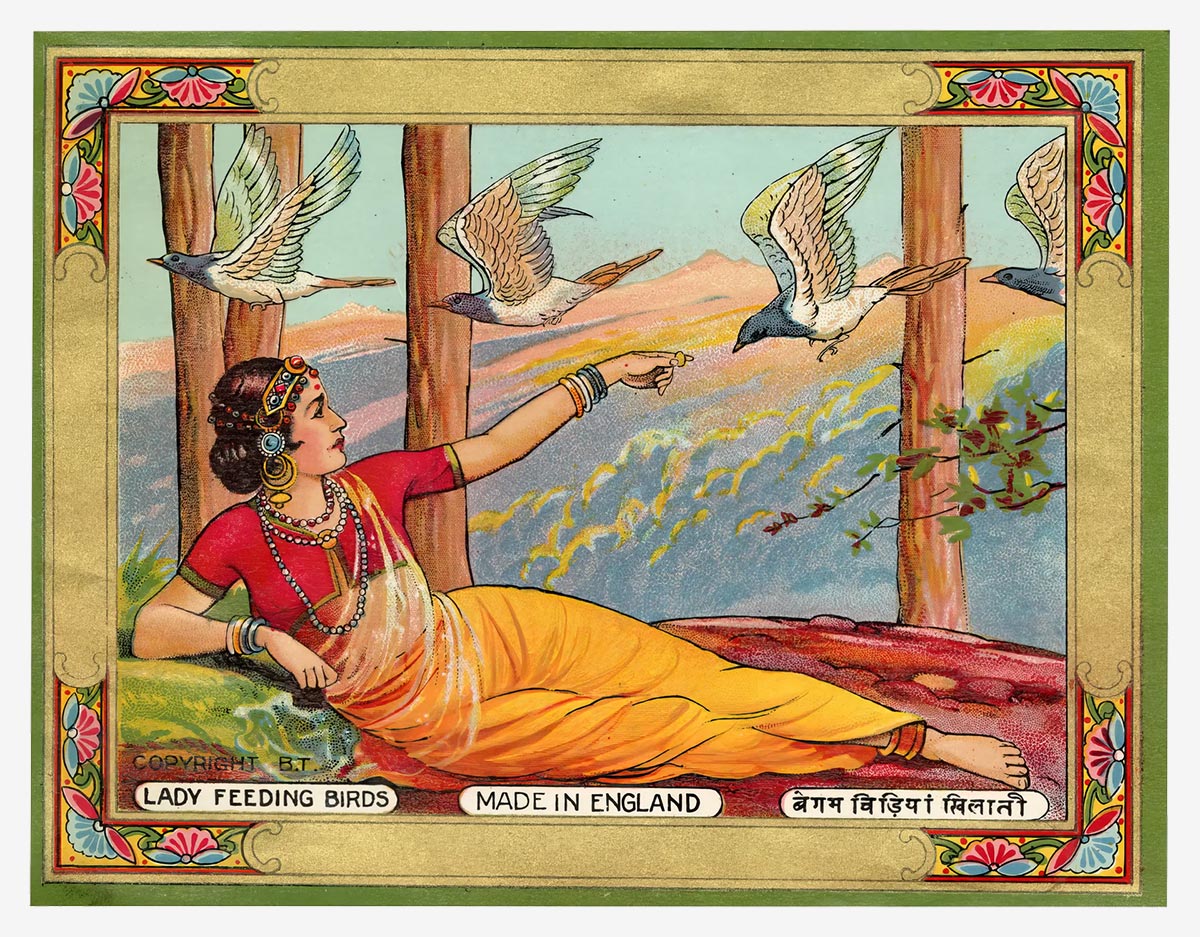

At first glance, the tikat is no larger than a postcard. These were printed in beautiful chromolithography, a brand-new colour printing technology that revolutionized printing in the 19th century. Tags like “Made in England” or the maker’s watermark were also mentioned in these tickets to distinguish the products from others available on the market. Through this exhibition, MAP attempted to situate these little tokens of history in the intersection of economic and socio-political history of colonial India. The labels were stuck on the topmost layer of a cloth, and they displayed information about the quality and origin of the fabric, transforming the act of purchase into an emotional exchange.

The motive of deploying these printed labels was to create a mass appeal across regions, religions, and people who spoke different tongues. By seeking the shelter of devotional imagery, imperial symbols, romantic scenes, and local motifs, the Britishers attempted to sanitize the notion of their products being “foreign” and package them in an Indian way, and let the Indian masses consume them. Through these ways, they made their products appear more relatable, appealing, legitimate, and desirable to the Indians. Thus, the Chaaps were foundational to India’s consumer culture, post-colonial studies, and global history of trade.

Desire or Deception?

The labels were a successful drive of visual diplomacy. Motifs of these labels ranged widely, often incorporating Hindu deities like Lakshmi (the goddess of wealth) and Saraswati, mythological scenes, portraits of Maharajas and British monarchs (sometimes seated on top of the world to symbolize colonial power), Indian monuments like the Taj Mahal, and exoticized images of women in lush gardens. In the opinions of scholars and critics, these Tikats and Chaaps were powerful colonial instruments that helped in ‘naturalizing’ the incoming influx of mill cloth into markets that were built on centuries of handloom production. Thus shaping of Indian consumer identity was made through making Indians consume foreign goods, packaged in Indian form.

These designs often involved explicit cultural appropriation or intellectual copying. Research reveals instances where ticket artists in England drew inspiration from sources including Indian miniature paintings, calendar art, and even contemporary American paintings. A label that replicated a scene by American artist Maxwell Parrish replaced the figures with women draped in a sari for the Indian market. This propounds the fact that the world of advertising operated on the principle of effective, albeit culturally uncontextualized, persuasion.

Threads of Empire and Resistance

As post-colonial scholars have rightly highlighted, the bright images actually conceal the dark economic reality of Britain’s cotton dominance, which was secured through high tariffs and coercive Company practices that dismantled India’s own handloom industry. One famous ticket, for the firm Shaw Wallace & Co., depicted the connection between “England” and “India” as a bridge formed by the company’s name, showing half-naked Indian men weighing massive quantities of textiles, dissipating the message that it was their backbreaking effort, not the white merchants’, that sustained the connection.

During the growing nationalist and Swadeshi movement, Indian mills began using labels that proudly featured Indian historical figures, sacred sites, and national symbols, appealing to consumers to support domestic production and protest against the consumption of foreign goods. This way, a colonial marketing tool transitioned into an emblem of national resistance.

Event Details

| Event | Details |

|---|---|

| Title | Ticket Tika Chaap: The Art of the Trademark in Indo-British Textile Trade |

| Venue | Museum of Art & Photography (MAP), Bengaluru |

| Dates | On view until February 15, 2026 |

| Timings | 10:00 AM – 6:00 PM (Closed on Mondays) |

| Curators | Nathaniel Gaskell and Shrey Maurya |

| Organised By | Museum of Art & Photography (MAP), Bengaluru, in partnership with Bank of America |

| Theme | Exploring 19th–20th century textile labels (tikats, tikas, chaaps) as early forms of branding, visual art, and cross-cultural communication in colonial India. |

| Medium | Chromolithographic prints on paper — used as textile labels on British and Indian mill-made cloth. |

| Official Website | https://map-india.org |

Key highlights

- The exhibition reframes tickets as early brand artifacts that shaped consumer perception in colonial India.

- Designs range from devotional imagery to imperial iconography, revealing how producers negotiated cultural difference.

- MAP pairs the show with public programming (guided walks, printmaker perspectives) and a substantial catalogue/book.

- Accessibility and inclusion are foregrounded: audio descriptions, ISL videos, and wheelchair access are part of the museum offering.

Reading the labels today

These labels display a continuity as contemporary brands and garment labelling still perform crucial tasks, as they build emotional associations between product and purchaser. The tickets are linked to the language of trust and offer a brand’s statement on fashion, labour, and transparency.

Takeaway

By bringing one of the most rudimentary materials from history, and presenting those before the masses does two things. It reimagines the neglected visual archive, and secondly, it reminds the audience of the persuasion that often happens at the scale of the intimate and the ornamental. By blending the sacred with the commercial and the colonial with the local, the textile ticket laid the foundations of mass visual communication in India. In the era of fast fashion and rebranding, the Chaap continues to signify a story that goes beyond the product.